Six Ways to Fix Illinois’ Self-Funding Loophole

One year after Governor Rod Blagojevich’s 2008 arrest on corruption charges, the Illinois General Assembly responded to calls for reform by establishing the state’s first campaign contribution limits. The law contained a caveat unique to Illinois: in any race with a so-called “self-funding candidate,” the limits would be lifted for all candidates.

The provision was intended to level the playing field between wealthy candidates, who the U.S. Supreme Court says may spend unlimited personal funds on their own campaigns, and their non-wealthy opponents, who would otherwise have to scrounge for contributions below the legal limits. It was also meant to protect opponents of candidates supported by independent expenditure groups, which can take in and spend unlimited amounts as well.

The law provides that in any statewide race in which a candidate donates more than $250,000 to their own campaign or an outside group spends at least that amount supporting or opposing them, the contribution limits come off. In non-statewide races such as those for state House and Senate seats, the triggering amount is $100,001.

Unfortunately, the self-funding provision inadvertently created a loophole that was ripe for abuse. As reported by Reform for Illinois and the Better Government Association, it has now become common practice for legislative leaders in both parties to donate or loan $100,001 to their own campaigns, triggering the self-funding provision and opening the floodgates to uncapped megadonor and special interest contributions.

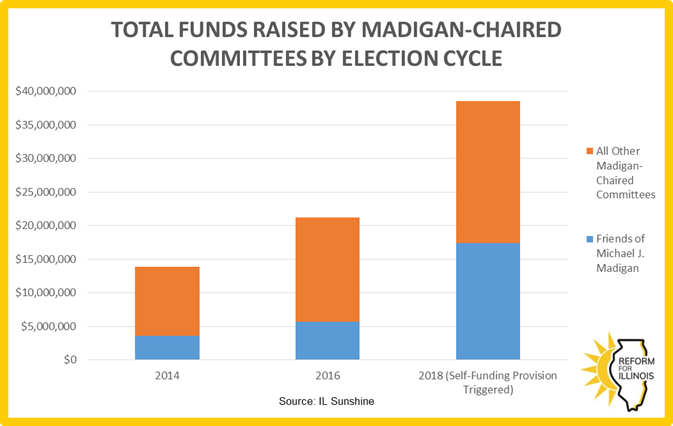

While the total amount of money raised by Madigan-chaired committees doubled between 2016 and 2018, contributions to his personal campaign committee more than tripled from $5.7 million to $17.4 million.

While the total amount of money raised by Madigan-chaired committees doubled between 2016 and 2018, contributions to his personal campaign committee more than tripled from $5.7 million to $17.4 million.

Legislative leaders don’t need the extra funds for themselves—none of them has faced a credible reelection threat in years. Instead, they use the money to further consolidate their power by transferring millions to grateful candidates either directly or using a state party committee as an intermediary.

For example, after Speaker Madigan triggered the self-funding provision in his race in 2018, he transferred nearly $6 million to the Democratic Party of Illinois and the Democratic Majority committees (both of which he controls), which then redistributed the cash to other House and Senate candidates.

Importantly, party committees can then contribute unlimited amounts to candidates in a general election, meaning the loophole effectively allows the leaders and their donors to circumvent the state’s contribution limits.

In addition to amplifying the power of party leaders, the self-funding loophole magnifies the influence of a small set of wealthy individuals and special interests—the opposite of the provision’s original intention. During the 2018 election cycle, eleven donors—ten unions and one hedge fund manager—gave $500,000 or more to Speaker Madigan’s committee, making up 56% of the roughly $17.4 million he raised. Meanwhile, after an outside group supporting House Minority Leader Jim Durkin triggered the provision, a $6 million donation from billionaire Kenneth Griffin to Durkin accounted for almost two-thirds of his total fundraising that cycle.

Fundraising by Legislative Leaders with Contribution Limits Removed from 11/9/2016 to 11/6/2018

| Total Raised | Total Raised from Donors Giving More Than $500,000 | Percentage of Total Fundraising from Donors Giving More Than $500,000 | |

| House Speaker Madigan | $17,414,572.14 | $9,735,200.00 | 56% |

| House Minority Leader Durkin | $9,150,617.20 | $6,000,000.00 | 66% |

| Senate Minority Leader Brady | $3,388,658.50 | $1,500,000.00 | 44% |

It’s sometimes used as intended

While the self-funding provision is easily exploited for the subversion of contribution limits in some cases, it arguably has served a legitimate purpose in other races. In this year’s race for Cook County State’s Attorney, Republican candidate Patrick O’Brien recently removed contribution limits in the races by donating more than $100,000 to his own campaign. Shortly afterwards, his Democratic opponent, Kim Foxx, took $100,000 donations from Fred Eychaner and Michael Sacks.

In the 2019 race for mayor of Chicago, five candidates contributed more than $100,000 to their own campaigns. Because contribution limits were removed, other candidates were able to match and even outraise the self-funders.

Similarly, in the 2018 gubernatorial primaries, Bruce Rauner and JB Pritzker spent tens of millions of dollars on their own races. While their spending massively outstripped their opponents,’ the ability of other candidates like Daniel Biss and Jeanne Ives to fundraise without limits kept their campaigns competitive. The provision still had questionable side effects in both the mayor’s and governor’s races—lifting caps escalated the money arms race and allowed megadonors like Griffin and some unions to dominate the fundraising game. But it also allowed some non-wealthy candidates to compete on a more level playing field.

A rule designed to even the odds between wealthy and ordinary candidates has become a loophole that consolidates the power of a few and incentivizes candidates to chase even more money from a small number of donors rather than spend time getting to know the needs of their constituents. But despite its exploitation, the self-funding provision has seen legitimate use as well.

How can Illinois balance the goals of giving candidates a fighting chance against wealthy opponents while also controlling the influence of a small number of rich donors, special interests, and party leaders?

Constitutional restrictions on reform

The question of how to respond to self-funded campaigns and well-funded outside groups comes from the U.S. Supreme Court’s current interpretation of the First Amendment, which holds that governments cannot cap candidates’ personal spending on their own campaigns. Nor can they limit contributions to or spending by independent expenditure committees.

A 2008 decision further restricted policy choices for solving the self-funding problem. Davis v. Federal Election Commission invalidated a portion of a federal campaign finance provision known as the “Millionaire’s Amendment” that aimed to level the playing field by lifting contribution limits for self-funders’ opponents but not for the wealthy candidates themselves. The Court held that regardless of the difference in resources among candidates, contribution limits could not be applied unequally.

Given these constraints, Illinois has limited options for addressing the issues caused by both unfettered spending and the self-funding provision’s unintended consequences. Below are some possibilities.

Option 1: Repeal it

Illinois is the only state that lifts contribution limits when a candidate decides to self-fund, making repealing the provision seem like an obvious option. Repeal comes with risks, however.

Restoring caps on everyone, regardless of self-funding status, could shift unlimited contributions to independent expenditure groups, which often have less stringent requirements on donor disclosure. Still, since such groups are supposed to be “independent,” this could potentially reduce the control a few party leaders have over the Illinois political ecosystem.

Perhaps more importantly, doing away with the provision would not solve the problem of leveling the playing field between independently wealthy candidates and their opponents. This is not a hypothetical concern in Illinois, given that the past two gubernatorial races featured multimillionaire and billionaire candidates who spent lavishly from their personal fortunes in both the primary and general elections.

Option 2: Raise—but do not remove—fundraising limits in a race where a candidate self-funds

Currently, when a candidate in a race donates or loans more than $100,000 to their own campaign, all donation limits for all candidates in the race are removed. As an alternative, Illinois could raise contribution limits without removing them entirely to give non-self-funding candidates the opportunity to raise more without flooding the race with vast amounts of money and elevating the role of megadonors.

This model of increased but not unlimited contributions was implemented at the federal level in the congressional Millionaire’s Amendment. (The Millionaire’s Amendment was only ruled unconstitutional because it applied different limits to wealthy and non-wealthy candidates. Symmetrically applied increased limits should be constitutional.) In Colorado, a proposed constitutional amendment to create a self-funding provision (which voters ultimately rejected) would not have removed contribution limits entirely but instead would have quintupled them, increasing the amount candidates could raise but still subjecting contributions to caps.

For example, Illinois could amend the self-funding provision to triple contribution limits, which would increase individual contributions from $5,800 to $17,400 and independent expenditure contributions from $57,800 to $173,400—substantial amounts, but still significantly less than the $864,200 that Mike Madigan received from the Engineers Political Education Committee in December 2019 shortly after he triggered the self-funding provision for his race.

This year, from the start of January through the end of August, the Friends of Michael J. Madigan campaign committee has received more than $4.6 million from 67 individuals, unions, businesses, and PACs. $4 million of its funds have come from 11 PACs that donated in excess of normal contribution limits. If contribution limits were tripled rather than eliminated, the committee would have raised about $2.2 million during that period.

Option 3: Raise the amount a candidate must self-fund to trigger the removal of contribution limits

Currently, contribution limits are lifted once a candidate gives a certain amount to their campaign: $250,001 for statewide races, and $100,001 for all other races. If these thresholds were higher, the self-funding provision would be more difficult to exploit. Candidates wishing to lift contribution limits on themselves would need to be able to donate or loan a significantly higher amount to their campaigns in order to do so.

The proposed self-funding rule considered in Colorado would have kicked in after a candidate contributed $1 million to their own campaign—a much higher trigger than Illinois’. With a higher trigger amount, Illinois could preserve the original purpose of the self-funding provision while making it more difficult—though certainly not impossible—to exploit.

Conversely, however, it could make the provision less effective at providing a safeguard for non-wealthy candidates to compete with self-funders. A candidate could donate $999,999 to their own campaign without triggering the self-funding provision. To match that, a non-self-funding candidate would need to find 173 individuals, 87 businesses, or 18 PACs willing to contribute their legal maximum amount.

A higher triggering amount would have to be carefully calibrated to deter abuse without hobbling non-wealthy candidates. But there is plenty of wiggle room between Illinois’ current thresholds and $1 million.

Option 4: Only remove contribution limits when candidates donate to their campaigns, rather than loan them money

Currently, any contribution to one’s own campaign committee will trigger the removal of contribution limits. That includes a loan. In December of 2019, State Senator Don Harmon loaned his committee $100,001, allowing it to collect as much money from individual donors as they were willing to give. The committee repaid the loan to Senator Harmon in June of this year. Similarly, in October of 2018, Senate Minority Leader Bill Brady loaned his campaign committee $100,001. Three days later, he received $500,000 from Kenneth Griffin. Brady repaid his loan with $1069.45 in interest two months later. (His committee has yet to repay the loan he just made to it this August.)

The barrier to blowing contribution limits is relatively low when candidates only need to loan their campaigns money and are confident that they will be able to repay them once they start raking in large donations. In practice, this means that the self-funding provision rewards wealthy candidates for being able to front a repayable loan of $100,001 to their campaigns. Non-wealthy candidates, meanwhile, would not have the ability to do so. This aspect of the self-funding provision is giving an additional fundraising option to wealthy candidates that they can choose when to trigger, the opposite of the spirit of the law.

Amending the self-funding provision so that it only triggers when candidates donate—rather than loan—money to their campaigns would not fully prevent abuse, but it could reduce its prevalence by increasing the cost of triggering it.* Furthermore, it would promote the spirit of the law, given that a candidate who temporarily loans their campaign money that will be paid back is not actually self-funding. On the other hand, it would give yet another advantage to even wealthier candidates—those who can afford to permanently lose $100,001 rather than just lend it.

Option 5: Limit party contributions to candidate committees

A major problem with Illinois’ self-funding provision is that it allows a candidate to raise unlimited funds and transfer them to a party committee, which can then donate unlimited amounts to its own candidates—even in races where contribution limits are still in place. This is only possible because Illinois does not place limits on the amount a party committee can donate to a candidate committee during the general election. (Contribution limits are in place during the primary but they are very high: $144,800 for Senate candidates and $86,900 for House candidates.) About half of states and the federal government impose some sort of limit on the amount that candidates may accept from political parties. Similarly, Illinois permits candidate committees to transfer unlimited funds to state party committees in general elections, meaning money flows without restriction in both directions.

Imposing limits on transfers between candidates and parties would reduce the incentive for a candidate to take advantage of the self-funding loophole to enrich their parties while leaving the provision available for candidates who need to raise additional funds to match a self-funder. Currently, the self-funding provision is most often used by legislative leaders in each party. Because leaders typically come from safe seats and do not often face competitive elections, they are free to fundraise aggressively and dole out unlimited donations to candidates in other races. Limits on party contributions to candidates—and vice versa—would reduce the effectiveness of this strategy.

Option 6: Implement a publicly financed Clean Elections program

The self-funding problem highlights the fact that in the leaky American campaign finance system, the money tap is hard to cap—donors will often manage to get that cash where they want it to go. That’s why jurisdictions around the country are turning to Clean Elections programs, which typically provide voters with matching funds for small donations or donation vouchers voters can give to the candidate of their choice. Rather than focus on capping contributions, these programs create a viable fundraising alternative for candidates who want to spend their time addressing the needs of their constituents instead of those of big donors and party elites.

Public financing would address the unintended consequences of the self-funding loophole by reducing candidates’ dependency on contributions from their respective political parties. Party support is not necessarily problematic. But when candidates rely too heavily on it, they are less likely to choose the interests of their constituents over the interests of the party establishment when the two are in conflict. That’s not healthy for democracy.

It won’t be easy

No solution to the self-funding quandary is perfect. But it may be time to start considering the possibilities of reforming a provision whose egalitarian spirit has been undermined by state leaders to concentrate power in the hands of a few.

Reform for Illinois will keep shining a light on the inner workings of our state government and advocating for common-sense campaign finance reforms that will ensure that everyone—not just the wealthy or well-connected—has a voice.

*Amending the self-funding provision to remove a loan as a trigger could still leave open a separate loophole; a candidate could donate $100,001 to their own committee, declare their campaign self-funded, and then refund the contribution, which would still be categorized as a donation and not a loan. This issue could be addressed by requiring that if a candidate returns the donations they listed on their self-funding disclosure form, then contribution limits in the race are put back in place, and the self-funding candidate must return any contributions in excess of the normal limits.

Prepared by RFI Policy Analyst Isaac Wink

Back